During our recent stay in San Pedro de Atacama, we were harassed by an overly friendly llama and a cat that wanted to sleep on our faces. One night we didn’t have hot water, the next we didn’t have any water at all. A dog barked continuously through both nights. Early on our last morning, I fell into a hole in the driveway and rolled into a clay oven. And when we were packing up to leave, as if in atonement for our suffering, we found a million Chilean pesos in a drawer. But let me start at the beginning.

We drove across the great north desert of Chile in a pickup truck, stopping at desert oases to sip fruit juices and swim in springs, pausing to gawk at the Andes, ghost towns, and giants etched into mountains thousands of years ago. The desert here is an alien environment, filled with mountains of different colors, colors I didn’t think could be found in nature…

There was also giant cacti… mammoth sand dunes…boiling water shooting out of the ground…and FLAMINGOS!!!

The tour through northern Chile was led by Adrian, a transplanted South African with a rakish sense of humor and energy as boundless as the Geysers de Tatio.

This is only one of three “tours” we’ve had so far in our four months of travel (the other were of the Amazon and the Galapagos), and it was unique in that it was just us and a guide for eight days. The kids have held up amazingly well through these busy times, but they have their limits, and we were definitely pushing them when we arrived in San Pedro de Atacama, a once-sleepy oasis town that has recently turned into a hub of tourism.

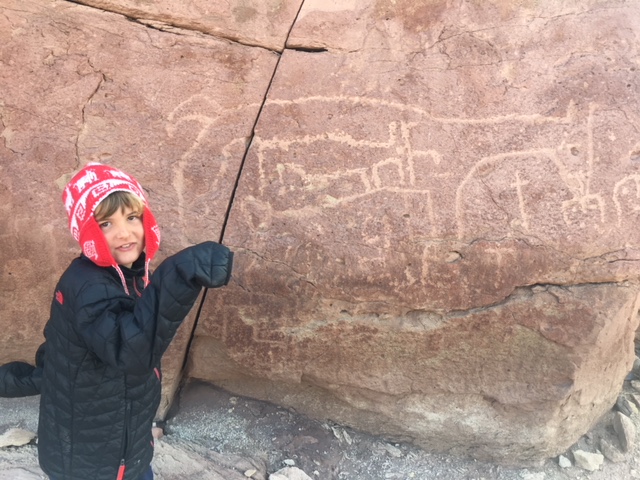

We arrived after a night of camping in a desert canyon, between a river and a cliff adorned with ancient petroglyphs of llamas, pumas, and caravan leaders.

To get to our campsite, we drove across an expanse of desert and through a canyon until we crossed a surprisingly wide (considering our desert surroundings) river. For L.A. people who rarely see the Milky Way, the stars that night were unbelievably bright. Instead of a dark sky broken up by a few tiny stars, it was more like an expanse of starlight broken up by a few tiny spots of darkness. I could spot a few constellations (they’re all backwards to us northern-hemisphere folk), but most of them were overwhelmed in cascades of stars I’d never seen before.

The overnight was well worth the hassle of setting up camp and taking it down, but we were all exhausted afterwards, the kind of exhaustion that makes you cry for no real reason and regret ever having left the familiar confines of Los Feliz (looking truer to its name every moment). We arrived in San Pedro de Atacama exhausted and incredibly, unspeakably dirty; the desert dust seemed to permeate every pore. We checked into our lodgings, a large house with two guest rooms on a large property populated by dogs, cats and two llamas. The male llama, named Santiago, was strangely human; he seemed less like an animal and more like foreigner with little sense of personal space zipped inside a llama costume.

He would approach you and smell you, bringing his huge-eyed face right up next to yours so that his eyelashes brushed up against your skin. It seemed more of an act of curiosity than of aggression, but coming from a three-hundred pound animal with a full set of teeth, it was hard to totally relax in his very close presence.

We were given a short introduction to our room by a hired hand — the family that lived there was out of town — who then took off. Sarah stepped into the shower and moments later I heard a string of profanity the likes of which I had never heard from the lips of my wife. She had just gotten soaped up when the water turned cold. I was given the mission to find hot water by any means necessary. We were all freezing and filthy.

I walked into the house, which seemed abandoned. “Hola?” I called out several times. From the recesses of the dwelling, an elderly woman emerged in a housecoat. I communicated the problem while she looked at me as if I was an unwanted intruder. It occurred to me as I labored through my Spanish description of our plight that the family had never told their grandmother that they had rented out a room to tourists. When I was done, she replied, “I know nothing about this” and proceeded to call her daughter. After a few moments of rapid conversation, I was led to a closet that contained a large metal butane canister. The old woman informed me that I was to hook it up to the house’s water heater. I told her I didn’t know how to do this. She made a face like she’d just tasted bad milk — since most water heaters run on butane in Chile, this must be something every male here over the age of 12 learns how to do — and, with unexpected strength, hoisted the butane canister, carrying it to the water heater. It took several more calls with her daughter to figure out its installation. At one point, La Senora put me on the phone with the daughter, who urged me in Spanish to “use great force” in attaching a valve to the canister’s head. Alas, in this too I was lacking, and La Senora, summoning decidedly non-grandmotherly strength, unceremoniously slammed the valve down onto the canister. Success. We were all able to take showers, though they were late at night and we were too tired to enjoy them.

The next morning we woke at 5 a.m. in order to visit the Geysers of Tatio, a plateau of volcanically heated water that bursts to the Earth’s surface. It’s impossible to describe the exhaustion we all felt, clambering out of our beds in the darkness and attempting some form of breakfast, but all travelers know it. Our guide Adrian picked us up at 5:30. The kids and Sarah got in his pickup. I stayed outside to close the driveway gate. As I stood in the darkness, waiting for Adrian to turn his pick-up around, I heard steps behind me and turned. Santiago the llama lurched towards my face for an early morning sniff. I stepped backwards and found myself falling and rolling down into a hole. At the time, it felt as if I was falling to the center of the Earth, but when I later had a look at the hole in daylight, I saw that it was only about six feet deep. Chileans often have brick ovens around their properties to cook food and burn garbage, and this was one of those. Miraculously, I was unhurt. I crawled out of the hole back onto the driveway and got into Adrian’s pick-up. “I just fell into a hole,” I said, to the amusement of everyone inside.

The geysers lived up to their hype — the sounds alone of the different bubbling waters was worth the trip — and Adrian took us around to the various water-spewing vents as we looked on in slack-jawed amazement.

The irony of hearing tales of tourists boiled alive for straying too far off the trail was not lost on me — the night before, we might have all plunged headlong into a geyser for a little hot water.

We capped off our tour of the Atacama by running half a mile down a giant sand dune. It felt like incredible freedom, letting gravity pull you down while the soft sand cushioned every step. We enjoyed a final dinner in San Pedro de Atacama (with my favorite Pisco Sours of the trip so far, made with the sweet local herb Rica Rica) and returned to our guest room. Imagine our dismay, standing in our sand-coated bodies, to find that now there was no water at all! I tried to find La Senora, but this time my frantic calls of “Hola?” went unheeded. Too exhausted to fight the fates that seemed determined to keep us dirty, we passed out in our beds. The next morning, miraculously, there was water — hot water — and we all were able to get clean before boarding our bus to northern Argentina. The woman who owned the house had appeared that morning and had figured out how to turn the water on again. We washed and packed. While doing a final sweep of the closets and drawers, Sarah discovered a huge stack of $10,000 peso bills in the drawer of our bedside table: A million Chilean pesos — the equivalent of around $1,600 U.S.

I’m not going to lie and say I didn’t think about keeping it. The discovery seemed to be a reward for having dealt with the lack of hot water, the lack of water, the nosy llama and the falling in the hole — not to mention the tourist fatigue and the everyday humiliations of awkwardly speaking a foreign language in a country I don’t understand. This was our payback. Time to book that five-star hotel in Patagonia!

The thing is, when you’re living on a travel budget, trying to cut corners and save money in the course of a six-month trip, it’s easy to lose sight of the big picture. A few times I’ve been penny wise but pound foolish. (A recent example: Last week, I drove an extra two hours and spent an hour at an airport rental-car counter trading our rental car in for something smaller and less comfortable in order to save…$200. Dumb). Would $1,600 help us on this trip? Undoubtedly. But…would it help us in our lives? Not really. And who knows who lost it, and how much it would help them get over their llama harassment and lack of water? As Sarah and I talked about it, I realized that there was something unseemly about travelling with another traveler’s money, something karmically damaging. And since we were about to embark on a nine-hour bus trip through the Andes to Argentina, it seemed a bad time to invite bad karma. So before we left for the bus station, under the watchful eyes of Santiago, we gave the house’s owner a thick wad of bills along with the debit card we found under it. She recognized the name on the card as the previous guest and promised to get in touch with him. We took her at her word and left for Argentina on a Pullman bus with bad sleep deprivation but good karma. And even though Julian threw up from altitude sickness when we crossed over the Andes, we arrived on the other side in one piece and considered ourselves blessed. Amen.