Before we leave Peru, I want to take a moment to remember some people who passed through our lives during our two months in this amazing country.

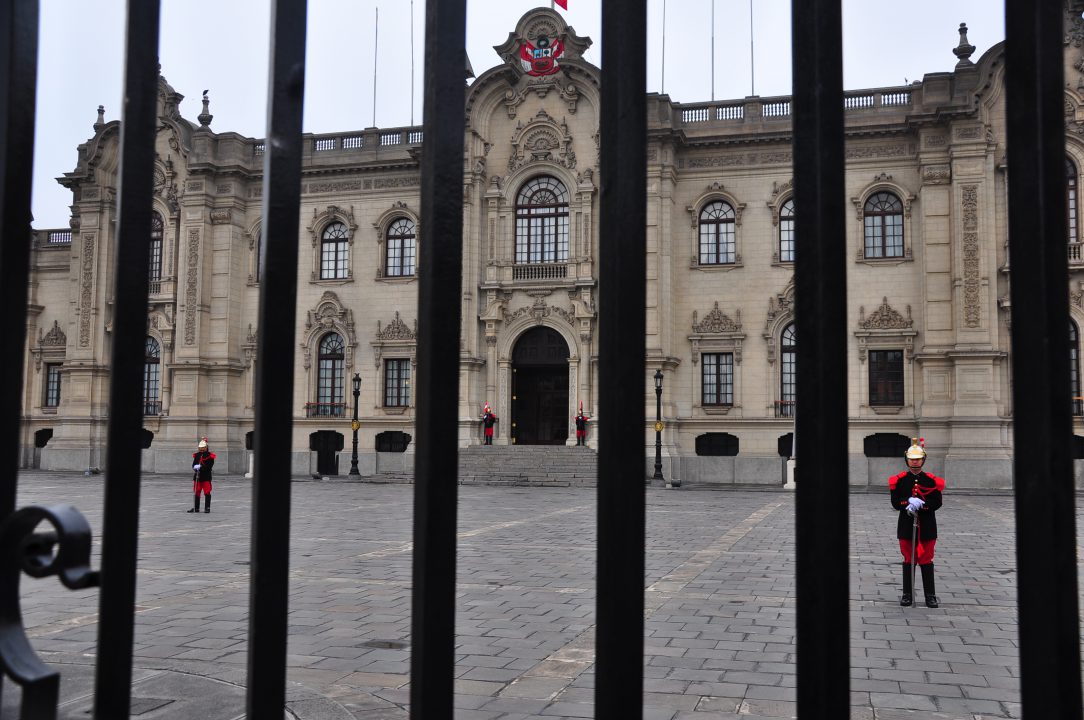

The Guard at the Presidential Palace

You know those very serious, unsmiling guards in front of presidential and governmental palaces? There were several of them in front of the presidential palace in Lima. Then, as we watched, one cracked a smile. Then laughed. What was going on? We approached the fence and saw that the guard was a woman, and her boyfriend was flirting with her through the rod-iron fence.

This summed up a lot of Peru for me: Cold and formal on the exterior, fun and playful on the inside.

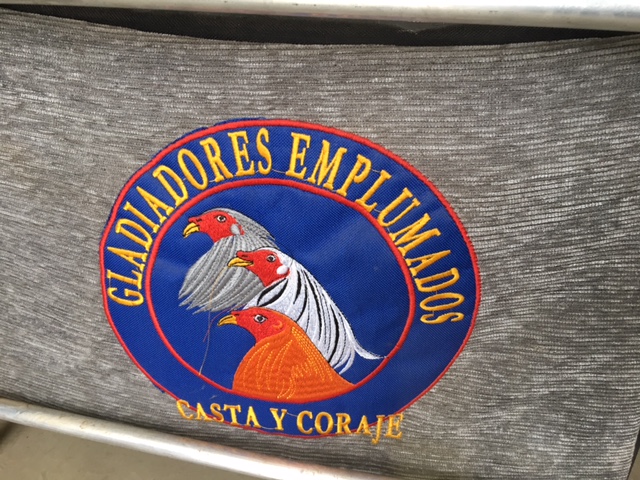

The Cockfighters

We spent a lot of time in Peru in buses and bus stations. In Chiclayo, waiting for our Trujillo bus, we met a man traveling with a wife, two kids and eight roosters. They were on their way to Cajamarca, where a big cock fight awaited. The roosters traveled in what looked like collapsible file folders. When they were inserted into their respective sleeves, they became quiet and docile. The man told me that the big money in Peruvian cockfighting wasn’t in the betting, but in the prize money. He and his family spent about half the year on the road entering their birds into various fights.

He showed us a video on his phone of one of his birds winning a fight. At first I thought I should shield the kids from it, but it turned out to be pretty boring, the way boxing is to someone not familiar with its rules and rituals. Our bus was called and we said good-bye to the family and their roosters.

The Paraglider Pilot

At Cleo’s urging, we decided to go paragliding off the cliffs overlooking the ocean in the Lima district of Miraflores. We assumed that Julian at 9 would be too young, then were told the minimum age is 5. (Welcome to Peru!). On the day we had enough cash (effectivo) to make the leap, however, we were told that it was windier than usual and that Julian might not be heavy enough. Then they matched him with the biggest, brawniest guy I’d seen in South America, complete with a crew cut, who looked like he just left special forces to pilot parachutes off a cliff in Lima. He gave Julian an amazing flight. At one point, Julian, Cleo and I were all aloft.

Afterwards, when we expressed surprise that Julian was able to go at all, his pilot showed us photos on his phone of him taking his five-month-old daughter paragliding. Wheeee!

(My pilot was less special forces and more Crazy McGillicutty, murmuring and mumbling behind me the entire flight. Perhaps he sensed the waves of terror that overtook me with every hairpin turn a hundred yards over the city and was attempting to soothe me by whispering sweet nothings in my ear?)

Carlos, the Amazon Guide/Aspiring Shaman

Carlos was our guide for six days in the Amazon jungle, and he helped us see sloths, caimans, five different species of moneys, pink dolphins, snakes, and more incredible birds than I could cram into my visual cortex. A local who’d grown up in a nearby village, he knew the jungle as if it were his backyard. Having said this, there was something a little, well, absent about him as a guide. He sometimes seemed disconnected from what we were doing. Part of this I chalked up to language issues — his English was leaky. But then one day, he took us to one part of the river to see the sunset. He soon revealed that he had also brought us to this spot because it enabled him to get cell phone reception — he was expecting some exciting news. After an animated phone conversation in the front of the boat, he told us what it was: He was going to be guiding an ayuhuasca ceremony in two days! Ayuhuasca is an hallucinogenic plant that grows in the rain forest, and the ceremony involves drinking it in a jungle hut, followed by vomiting, diarrhea and hallucinations galore that, if properly guided (according to Carlos), lead to “the truth about your past, present and future.” (I’d be into it if not for the vomiting, diarrhea and truth.) Not only were these ceremonies Carlos’s passion, leading them was far more lucrative than leading us into the jungle. Apparently, tourists were prepared to pay much more to explore the recesses of their consciousness than the Amazonian rain forest.

Carlos’ euphoria was short lived, however. He was a half-hour late for our night excursion and when he showed up, he looked downcast. Apparently, when the owners of the lodge we were staying in had found out about his new gig, they’d reminded him that he had an obligation to the lodge and couldn’t take off at the drop of a hallucinogen to run a ceremony. Carlos claimed that he was okay with losing the job, but he was never the same guide after receiving this news. To add injury to insult, that night he was stung by a nocturnal wasp who was attracted to the spotlight we’d asked him to hold on the boa constrictor he’d found dangling from a tree. We apologized as he clutched his hand in agony, but he smiled through his tears and mumbled, “It’s my job.”

Here Carlos does an impromptu “cleansing ceremony” in the jungle on my dirty, dirty human form.

Julian disagreed with a lot of what I’ve written above. Here is Julian’s response to “Carlos: Amazon Guide/Aspiring Shaman”: “Dad makes Carlos sound like a bad guide but he wasn’t. He let me play with his machete and he was always there for us. I liked Carlos more than I think anybody else did. I think he spoke great English and that Dad is skipping through big chunks of time. It was four whole days before he showed us the sunset, and he actually did want to show us the sunset, it wasn’t just to get cell phone service. And when Carlos was late, that was about another two days later, and when he got stung by a wasp, that was the same night.”

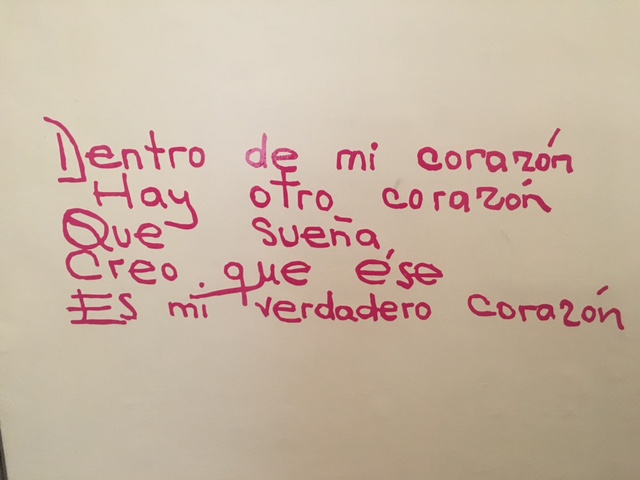

Luis Hernandez

I met this Peruvian poet through a special exhibition at the Casa de la Lituratura Peruana, a beautiful old building (formerly a train station) in Lima’s center. In addition to a poet, Luis was a doctor and a scientist, and his poems are filled with humor and metaphysics and raw emotion. He wrote on a giant roll of butcher paper he stretched across his house, filling it with words and drawings, and some of the paper was stretched across the length of the exhibition hall. As with many great poets, life off the page proved too much for him, and after years of being tormented by mental illness, he jumped in front of a train Buenas Aires, where he’d gone to get medical attention. He was 37. Stumbling onto this exhibition of his work, a sort of living tombstone, was one of the highlights of our trip for me, mainly because of how unplanned it was. I love it when travel opens you up to the lightning of random inspiration.

Alonso Cueto

Alonso is a very-much-alive Peruvian writer, a novelist (read “The Blue Hour” if you haven’t already) I was introduced to through a mutual friend. We met in an old cafe in Miraflores where the waiters look like they’ve been wearing the same uniforms since the 1940s. Speaking with Alonso about Peru and about writing was a revelation. I sometimes convince myself that my Spanish is passable, but after talking to Alonso (who speaks excellent English, having attended college in the US), I realized how starved I was for articulate insight into the culture I was experiencing. I somehow also feel obligated to mention that he was the tallest Peruvian I’ve ever met.

The Guard at Larco Herrera

One day in Lima, we left our apartment to see the Museo Larco Herrera, a much-recommended museum of pre-Columbian art. The first hurdle, getting a taxi, proved daunting, as none of the drivers we stopped seemed to know of the museum. Finally, we found a driver who’d heard of it, and though the price he quoted was high (in Peru, every taxi fare has to be negotiated, something I won’t miss), we felt like we had to take it. Twenty minutes later, we were dropped off at a large gate with a guard house. We paid our driver and got out, but when we approached the guard house, the uniformed guard on duty regarded us incredulously. “Children can’t come in here,” she said.

I was confused by this at first, then realized this policy must have something to do with the museum’s extensive erotic pottery collection. (I’ve discovered that this sort of collection isn’t unusual: The ancient people of Peru seem to have left behind an amazing array of pornographic pottery.) I told the guard (in my inconsistent Spanish) that she didn’t need to be concerned, that we wouldn’t be taking the children into the gallery that housed the pot porn. The conversation continued for a few more minutes before we realized that instead of a museum, we’d been brought to a mental hospital with the same name as the museum.

Hospital Larco Herrera is unfortunately at the other end of Lima from Museo Larco Herrera, and it took another twenty minutes and many soles to rectify the mistake by our first driver. The museum was worth the effort, but I hope we never visit the hospital again.

The Pop Star in the Jungle

We landed at the Iquitos Airport in a state of shock, a combination of having spent the previous day on a bus and the transition from chilly, coastal Lima to the hot, impossibly humid Amazon jungle. To add to our disorientation, the tour company that was supposed to pick us up at the airport was a no-show. While I searched the signs at the arrival gate in vain for our names, screams punctuated the opening of the airport’s automatic doors. Eventually, as we emerged into the brilliant sun with our baggage, the screams became constant and it finally occurred to me something horrible may be happening. Just the opposite, as it turned out: The screams marked the arrival of Columbian pop star Alejandro Palacio, who was giving a concert in Iquitos that night. The screams were provided by two dozen middle-aged female fans. Our concerns about being abandoned at a jungle airport momentarily melted away as we watched the singing sensation preen and pose for his fans.

I eventually was able to reach a representative of our tour company, who told me there’d been a mix up and that we should take a taxi into town. The only available cab was a beat-up compact from the 1960s literally held together with wire. The elderly driver was ingenious in fitting our bags into the trunk, and we crammed into the vehicle which coughed and sputtered into town, passing, momentarily, the large white bus hired to deliver Alejandro Palacio to his gig.