I met Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele five years ago, in my manager’s office. They were looking for showrunners for a sketch-comedy project they were developing for Comedy Central.

My writing partner, Ian Roberts, and I had done a few sketch shows between us and were looking for work. The meeting was supposed to last an hour; I remember looking at my phone afterward and being surprised that two and a half hours had slipped by. Keegan, effortlessly ebullient even on his worst days, is probably the easiest person in the history of civilization to have a conversation with; Jordan, introverted even on his most outgoing days, spoke less, but everything he said was interesting. Like a chess grandmaster, he seemed always to be five moves ahead of everyone else. I wanted to understand that brain. What the hell was going on in there?

We shot the pilot for “Key & Peele” in an abandoned detention center for juvenile delinquents. In a dilapidated cellblock, we staged a sketch in which Jordan, as Lil Wayne, was repeatedly stabbed with a shiv by an inmate, played by Keegan. I remember feeling haunted by the spirits of the unhappy boys who had been incarcerated there. Lil Wayne got stabbed again and again, Jordan emitted a high-pitched squeal, and I laughed at every take. Ah, comedy.

Despite being infused with unhappy boy ghosts, the pilot was picked up for series, and we shot seven more episodes. The ratings were only fair. Most people I knew who watched “Key & Peele” watched it on their computers, which do not count toward ratings. If people talked or wrote about the show, it was usually with a focus on race. Personally, I’ve always thought our primary subject matter was masculinity: what it means to be a man, what we can and can’t say. The scared husbands whispering “Bitch,” the vain slaves on the auction block, the hit man crapping his pants, Lil Wayne rapping in the cellblock, the two businessmen competing to eat the most disgusting soul food—they’re all fronting, trying desperately to be braver, cooler, smarter, and stronger than they really are. Fronting continued to be our meat and potatoes for the next four seasons.

Back then, of course, we didn’t even know if we’d get a second season. When Comedy Central decided to renew the series, they wanted to première the second season in January of 2013. I pushed for an earlier air date. During the first season, the sketch that got us the most attention was President Obama and his anger translator, Luther, but we couldn’t bring those characters back in January, because we wouldn’t know the results of the 2012 election when we were shooting. The network agreed to start us in October, before the election. We created two-minute “holes” in each episode, which we proceeded to fill with Obama-Luther sketches, shot at the last minute on an Oval Office set built in our reception area. For the episode airing the day after the election, we shot three sketches: one in case of an Obama victory, one for an Obama defeat, and one for a contested result. The defeat sketch was actually the funniest, with Luther destroying the set in anger at the loss. Fortunately, we didn’t have to use it.

The second season is when I first detected a shift. People were still mostly watching us on computers (which they would continue to do throughout our run and, most likely, for the rest of time), but they were watching us in greater numbers. One sketch, “Substitute Teacher,” with Keegan playing a black teacher in a white school who can’t get his students’ names right, climbed to sixty million views (it now has more than eighty-three million). The next viral sketch was “East-West Bowl,” in which college-football players introduced themselves with names like L’Carpetron Dookmarriot and Javaris Jamar Javarison-Lamar. We briefly considered that perhaps the ultimate secret to comedy success was sketches consisting of funny names, then moved on, determined not to repeat ourselves—or at least not to repeat ourselves too often. We chose not to emulate shows like “Saturday Night Live” and “Mad TV,” which made a business out of recycling characters and situations, unless we thought we could beat the original sketch.

President Obama told an interviewer that he liked the show. People started recognizing Jordan and Keegan at airports. For a while, they could preserve their anonymity in a boarding lounge if they stayed away from each other—as solo acts they remained unrecognized—but then even that stopped working. Walking down the street with Jordan and Keegan meant being showered with yells of “Ba-lak-ay!” and “Biiiiiiiiitch!” Strangers rushed up to them with huge smiles on their faces and hugged the pair as if they were long-lost siblings. Jordan and Keegan took all of this in stride, for the most part. I both envied and pitied them. Mostly, I envied them.

The next three seasons are a blur. I was in new territory as a writer-producer: getting past a second season on a TV show, for me, was the equivalent of a sixteenth-century European explorer making it to the Pacific, but with better snacks. I couldn’t believe my luck and couldn’t believe how tired I was. “Key & Peele” was always a grind to produce. Ten episodes could take a year: three months of writing, one month of pre-production, three months of shooting sketches, two months of editing them, a month shooting the wraparounds, another two months of putting it all together, mixing, etc., and then starting all over again. Just writing that last sentence (and, probably, reading it) brought back the feeling of perpetual exhaustion.

Every year, we started the writing process by casting the widest net possible, including any idea that intrigued us (we typically wrote five times as many sketches as we needed). From there on, producing the show was a process of mercilessly winnowing down the material: cutting sketches, rewriting the ones that survived, and, later, editing each scene until we felt that what remained was the essence of what had intrigued us in the first place. And, of course, the dick jokes.

Sketch shows, by definition, are uneven; that’s just the nature of the beast. No sketch is part of any larger story, and there’s no suspense to take you through them. Every time you begin a new sketch, you have a new opportunity to succeed or fail. That’s a lot of pressure, and it can get to you after a few seasons. The higher you set the bar, the more pressure you feel. We worked hard to achieve a low clunkers-per-great-sketch average, the ratio that, for me, distinguishes great sketch shows from the rest. I’m proud that most of our clunkers were sketches in which we were trying something we hadn’t tried before, and that we rarely played it safe. If we weren’t taking a risk in the writing, we were trying to do something we hadn’t done before in production or with special effects. I think artistic risk is undervalued in the entertainment industry. But I won’t defend “John From Cincinnati.”

The irony is that most people who watched the show never saw the actual “show” but rather cherry-picked the sketches they wanted to see on their computer. This, I suppose, is another, less admirable way of achieving consistency.

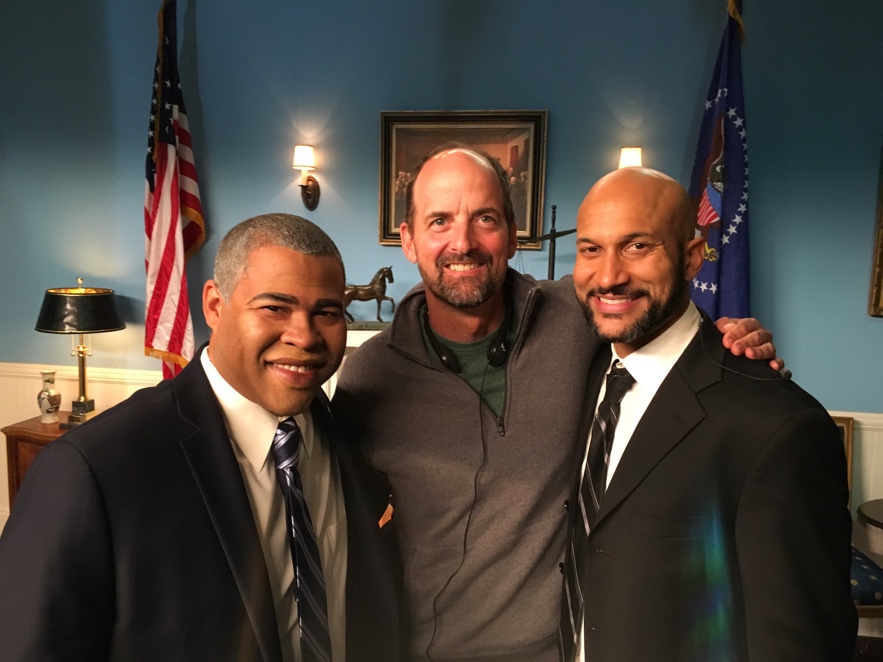

What I loved was watching the germ of an idea, discussed while waiting for the bathroom, turn into a gorgeously shot and hilarious sketch. I loved working with our writers, our production crew, our director, Peter Atencio, and our editors, who brought their own unique personalities to bear on the material. In every phase of the process, there were opportunities to turn an average sketch into a great one (and also to do the opposite, but I’m deluded enough to believe that I never engaged in that kind of reverse alchemy). Witnessing that transformation never got old. I also never got tired of arriving on the set to discover Jordan and Keegan, virtually unrecognizable in applied facial hair and wardrobe, instilling life into characters that, until then, I had known only on the page.

Last year, Jordan and Keegan decided that they’d had enough of the grind. I was the last to move out of our offices, empty except for the rented furniture, a few yellowing “Key & Peele” posters, and an odd assortment of unclaimed props and costumes: a football helmet with a robot on it, a Barbie doll made to look like a gangster. When I was a kid, my parents split up, and my mom was depressed most of the time. I spent a lot of energy trying to get her to laugh, and when she did, for that moment, everything was fine. “Key & Peele” gave me a chance to play out the dynamics of my dysfunctional childhood with an audience of millions. And, for five years, everything was fine.